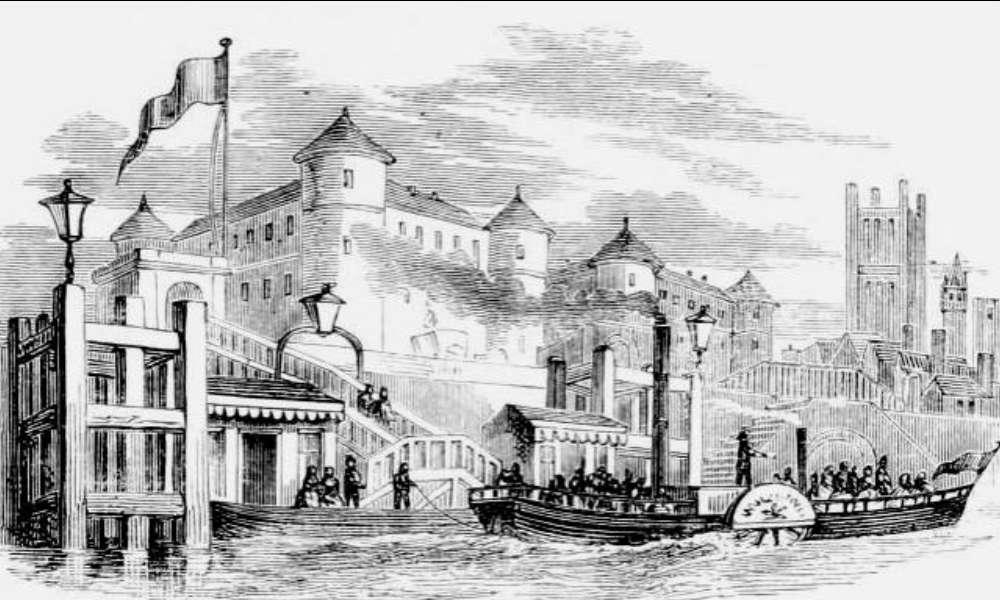

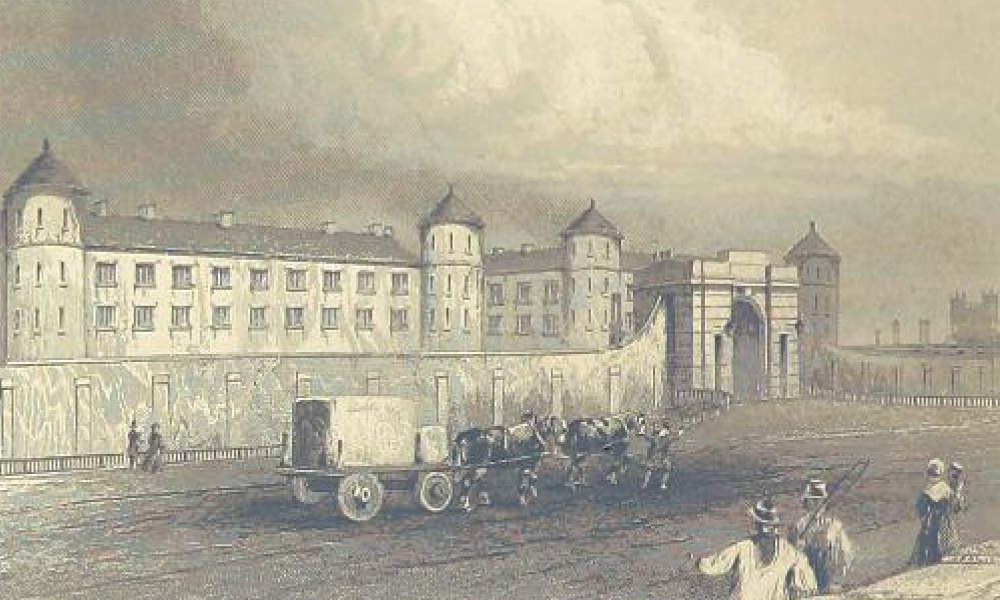

Long before the Tate Gallery and the Millbank housing estate stood on the Thames’ banks, this corner of London was home to a vast, intimidating prison. Millbank Prison was Britain’s first modern penitentiary, a bold experiment in reform and control, where architecture and ideology collided with the harsh realities of disease, labour, and overcrowding.

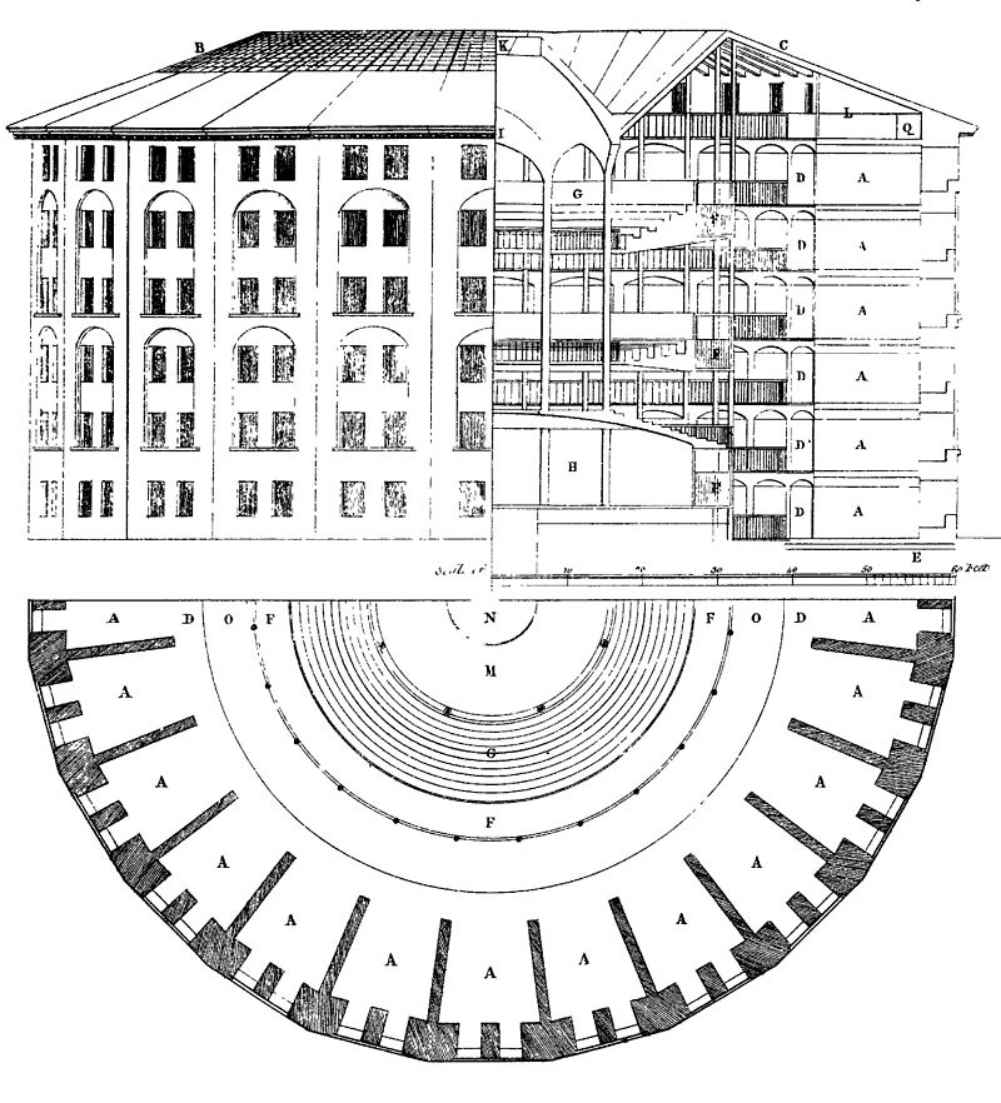

The site was deliberately isolated. Jeremy Bentham, the social reformer behind the original vision, believed that well‑regulated work and religious instruction could rehabilitate criminals. His plan, the Panopticon, proposed a circular prison with cells facing a central watchtower, giving the illusion of constant surveillance. Guards could theoretically see every inmate, and prisoners would never know if they were being watched. The design never came to fruition, but Bentham’s ideas shaped the minds of the architects who followed.

Design

Bentham’s original vision of having a Panopticon building was scrapped in 1812. The idea was to have a round prison with cells on the circumference facing a core at the centre. The guards were to sit in the central core and view all cells, thereby giving the illusion of constant surveillance.

A competition to design what would be Britain’s new and largest national correctional facility was held and after 43 entries the winning design went to William Williams who based the design on Bentham’s principles. It was adopted by practising architect Thomas Hardwick. However, Hardwick was not able to complete the project and resigned in 1813. John Harvey was then given the job but was dismissed in turn in 1815. Millbank was finally completed in 1821 by Robert Smirke.

The muddy marshy area on which the prison stood gave architects and builders a lot of headaches from the outset as the building’s foundations kept subsiding (hence the succession of architects). After several attempts and with £500,000 added to the original estimate, Robert Smirke solved the problem by introducing a new and unique concrete raft to provide a secure foundation.

History

Both male and female prisoners were incarcerated in Millbank, with the women arriving first in June 1816. Male convicts initially began arriving the following year, in January.

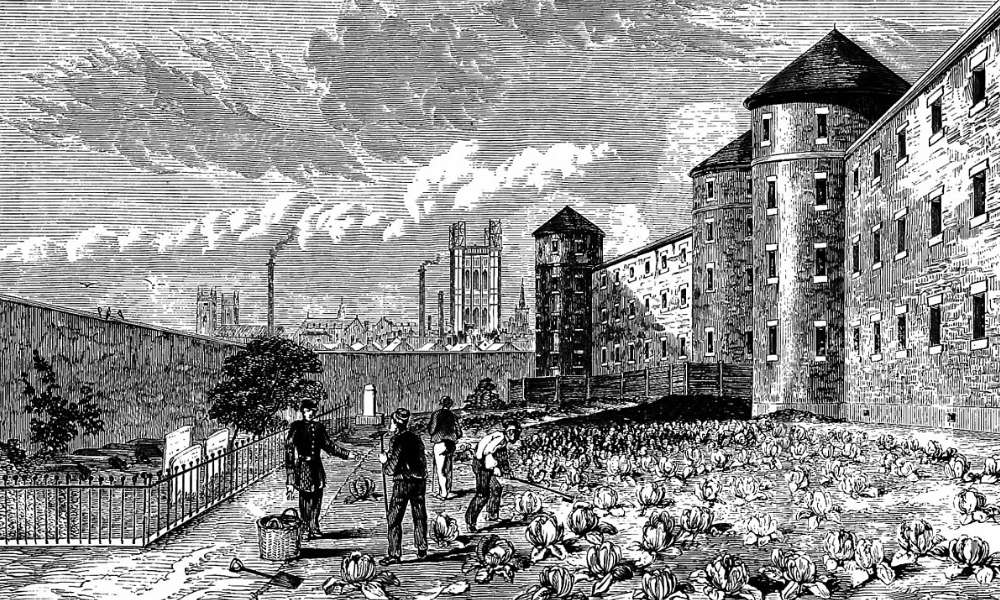

Five-ten-year tariffs could be imposed on those prisoners thought to be ripe for reform, as opposed to transportation to Australia. However, the facility was used to hold felons prior to transportation too, especially in its later history, when it was deemed a failure in its intended purpose of reformation.

For those incarcerated within its walls, life at Millbank was grim. Prisoners were not permitted to speak to one another or socialise in any way for the first half of their sentences. Masks were worn so they could not see each other’s faces during exercise periods and there was a single cell occupation rule throughout the prison. Non-productive tasks, such as turning a screw until it clicked, were doled out and the prisoner was expected to achieve a certain number of revolutions until they were permitted to stop. Treadmills were also employed.

It was thought that these measures coupled with strict religious instruction, would promote an ethos of hard work and reflection upon one’s misdemeanours on the part of the inmates.

However, flaws in both the design of the building and its location did not assist in reforming prisoners in the manner that was originally intended. The maze of corridors was so lengthy that warders often became lost going about their duties. Additionally, the ventilation channels allowed sound to travel, thus the inmates found a way of communicating.

The site was a further problem, in that its location directly on the marshy banks of the Thames allowed the disease to run rife. 1822/3 saw the rapid spread of a deadly Cholera epidemic. Reports of Scurvy and Dysentery were also reported. Depression was also commonplace, perhaps not surprisingly.

Another disadvantage was that the cost of running such a vast building proved to be unsustainable.

Added together, these factors eventually sealed the fate of Millbank Penitentiary. After 1886 no more prisoners were held within the walls of the prison, with its eventual closure in 1890. Two years later it was finally demolished.

Why Millbank Prison Matters

Millbank Prison was more than bricks and cells. It was Britain’s first attempt at a modern penitentiary, a place where philosophy met the stark reality of human behaviour. It influenced future prisons, introduced the idea of structured rehabilitation, and left a mark on the London cityscape. Walking past the Tate or the Millbank Estate today, it is easy to forget the prisoners, the hard labour, and the disease that once defined this site.

Millbank Prison is a reminder of the ambition and flaws of early Victorian reform, and the enduring influence of Bentham’s ideas on modern criminal justice. It may no longer hold prisoners, but its story still resonates in the city it helped to shape.

The Location Today

Today passersby may not recognise the red-bricked housing estate that stands in its place, or indeed the onetime army barracks, now an art college. They may, however, be familiar with the Tate Gallery, its grand entrance stands upon the very spot where one would have entered Millbank Prison and some of the bricks from the penitentiary were used in its construction. Some reports suggesting that the Millbank housing estate was also constructed of bricks from the prison are unlikely to be true since the estate is built entirely of red brick. Millbank prison was built in yellow brick.

If you walk down John Islip Street towards Cureton Street, you can still see the remains of the moat, which surrounded the prison. Pictures below.

Millbank Prison Described by Charles Dickens

A sluggish ditch deposited its mud at the prison walls. Coarse grass and rank weeds struggled over all the marshy land in the vicinity. In one part, carcasses of houses, inauspiciously begun and never finished, rotted away.

– Charles Dickens, David Copperfield

What also is not widely known and probably secret at the time.(maybe until now )The gasometers behind the building went many feet below the ground and during the 1930s along with other gasometers were covered up and converted to deep bomb shelters and command centres ready for the coming war the government envisaged with many air raids.

As many government buildings nearby they may still be there! Not far away

on the junction of Monck Street SW1 and Great Peters Street SW1 was the Rotunda nuclear bomb shelter(I went inside as used as a civil service club and rifle range in the 70s when a family member was a member.) on the site of the former gasworks were removed in the last few years and last used as a command post in the First Gulf War. Government buildings replaced it. Who knows what is underneath now?

Thanks for that. I didn’t know the gasometers went so far underground or were converted into bomb shelters and command centres. The Rotunda example is really interesting, especially being used as a civil service club and rifle range later on. Makes you wonder what might still be underneath London today.